Writing the Cyclone Scheme Compiler

by Justin Ethier

This document covers some of the background on how Cyclone was written, including aspects of the compiler and runtime system.

Before we get started, I want to say Thank You to everyone that has contributed to the Scheme community. At the end of this document is a list of online resources that were the most helpful and influential. Without quality Scheme resources like these it would not have been possible to write Cyclone.

In addition, developing Husk Scheme helped me gather much of the knowledge that would later be used to build Cyclone. In fact, the primary motivation in building Cyclone was to go a step further and understand not only how to write a Scheme compiler but also how to build a runtime system. Over time some of the features and understanding gained in Cyclone may be folded back into Husk.

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Source-to-Source Transformations

- C Code Generation

- C Runtime

- Data Types

- Interpreter

- Macros

- Scheme Standards

- Future

- Conclusion

- References

Overview

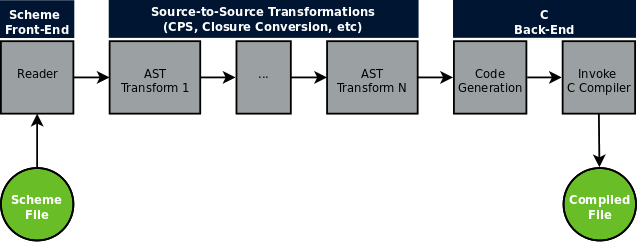

Cyclone has a similar architecture to other modern compilers:

First, an input file containing Scheme code is received on the command line and loaded into an abstract syntax tree (AST) by Cyclone’s parser. From there a series of source-to-source transformations are performed on the AST to expand macros, perform optimizations, and make the code easier to compile to C. These intermediate representations (IR) can be printed out in a readable format to aid debugging. The final AST is then output as a .c file and the C compiler is invoked to create the final executable or object file.

The code is represented internally as an AST of regular Scheme objects. Since Scheme represents both code and data using S-expressions, our compiler does not have to use custom abstract data types to store the code as would be the case with many other languages.

Source-to-Source Transformations

My primary inspiration for Cyclone was Marc Feeley’s The 90 minute Scheme to C compiler (also video and code). Over the course of 90 minutes, Feeley demonstrates how to compile Scheme to C code using source-to-source transformations, including closure and continuation-passing-style (CPS) conversions.

As outlined in the presentation, some of the difficulties in compiling to C are:

Scheme has, and C does not have

- tail-calls a.k.a. tail-recursion optimization

- first-class continuations

- closures of indefinite extent

- automatic memory management i.e. garbage collection (GC)

Implications

- cannot translate (all) Scheme calls into C calls

- have to implement continuations

- have to implement closures

- have to organize things to allow GC

The rest is easy!

To overcome these difficulties a series of source-to-source transformations are used to remove powerful features not provided by C, add constructs required by the C code, and restructure/relabel the code in preparation for generating C. The final code may be compiled direcly to C. Cyclone also includes many other intermediate transformations, including:

- Macro expansion

- Processing of globals

- Alpha conversion

- CPS conversion

- Closure conversion

The 90-minute scc ultimately compiles the code down to a single function and uses jumps to support continuations. This is a bit too limiting for a production compiler, so that part was not used.

C Code Generation

The compiler’s code generation phase takes a single pass over the transformed Scheme code and outputs C code to the current output port (usually a .c file).

During this phase C code is sometimes returned for later use instead of being output directly. For example, when compiling a vector literal or a series of function arguments. In this case, the code is returned as a list of strings that separates variable declarations from C code in the “body” of the generated function.

The C code is carefully generated so that a Scheme library (.sld file) is compiled into a C module. Functions and variables exported from the library become C globals in the generated code.

C Runtime

A runtime based on Henry Baker’s paper CONS Should Not CONS Its Arguments, Part II: Cheney on the M.T.A. was used as it allows for fast code that meets all of the fundamental requirements for a Scheme runtime: tail calls, garbage collection, and continuations.

Baker explains how it works:

We propose to compile Scheme by converting it into continuation-passing style (CPS), and then compile the resulting lambda expressions into individual C functions. Arguments are passed as normal C arguments, and function calls are normal C calls. Continuation closures and closure environments are passed as extra C arguments. Such a Scheme never executes a C return, so the stack will grow and grow … eventually, the C “stack” will overflow the space assigned to it, and we must perform garbage collection.

Cheney on the M.T.A. uses a copying garbage collector. By using static roots and the current continuation closure, the GC is able to copy objects from the stack to a pre-allocated heap without having to know the format of C stack frames. To quote Baker:

the entire C “stack” is effectively the youngest generation in a generational garbage collector!

After GC is finished, the C stack pointer is reset using longjmp and the GC calls its continuation.

Here is a snippet demonstrating how C functions may be written using Baker’s approach:

object Cyc_make_vector(object cont, object len, object fill) {

object v = nil;

int i;

Cyc_check_int(len);

// Memory for vector can be allocated directly on the stack

v = alloca(sizeof(vector_type));

// Populate vector object

((vector)v)->tag = vector_tag;

...

// Check if GC is needed, then call into continuation with the new vector

return_closcall1(cont, v);

}

CHICKEN was the first Scheme compiler to use Baker’s approach.

Data Types

Objects

Most Scheme data types are represented as allocated “objects” that contain a tag to identify the object type. For example:

typedef struct {tag_type tag; double value;} double_type;

Value Types

On the other hand, some data types can be represented using 30 bits or less and can be stored as value types using a technique from Lisp in Small Pieces. On many machines, addresses are multiples of four, leaving the two least significant bits free. A brief explanation:

The reason why most pointers are aligned to at least 4 bytes is that most pointers are pointers to objects or basic types that themselves are aligned to at least 4 bytes. Things that have 4 byte alignment include (for most systems): int, float, bool (yes, really), any pointer type, and any basic type their size or larger.

Due to the tag field, all Cyclone objects will have (at least) 4-byte alignment.

Cyclone uses this technique to store characters. The nice thing about value types is they do not have to be garbage collected because no extra data is allocated for them.

Interpreter

The Metacircular Evaluator from SICP was used as a starting point for eval.

Macros

Explicit renaming (ER) macros provide a simple, low-level macro system without requiring much more than eval. Many ER macros from Chibi Scheme are used to implement the built-in macros in Cyclone.

Scheme Standards

Cyclone targets the R7RS-small specification. This spec is relatively new and provides incremental improvements from the popular R5RS spec. Library (C module) support is the most important but there are also exceptions, system interfaces, and a more consistent API.

Future

Andrew Appel used a similar runtime for Standard ML of New Jersey which is referenced by Baker’s paper. Appel’s book Compiling with Continuations includes a section on how to implement compiler optimizations - many of which could be applied to Cyclone.

Conclusion

From Feeley’s presentation:

Performance is not so bad with NO optimizations (about 6 times slower than Gambit-C with full optimization)

Compared to a similar compiler (CHICKEN), Cyclone’s performance is worse but also “not so bad”:

$ time cyclone -d transforms.sld

real 0m6.802s

user 0m4.444s

sys 0m1.512s

$ time csc -t transforms.scm

real 0m1.084s

user 0m0.512s

sys 0m0.380s

Thanks for reading!

Want to give Cyclone a try? Install a copy using cyclone-bootstrap.

References

- CONS Should Not CONS Its Arguments, Part II: Cheney on the M.T.A., by Henry Baker

- CHICKEN Scheme

- Chibi Scheme

- Compiling Scheme to C with closure conversion, by Matt Might

- Lisp in Small Pieces, by Christian Queinnec

- R5RS Scheme Specification

- R7RS Scheme Specification

- Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, by Harold Abelson and Gerald Jay Sussman

- The 90 minute Scheme to C compiler, by Marc Feeley